Every

now and then, successful films make the novels upon which they were based

superfluous. Most everyone has seen some

version or another of such classic novels as Pride and Prejudice or David

Copperfield, but very few crack the original texts.

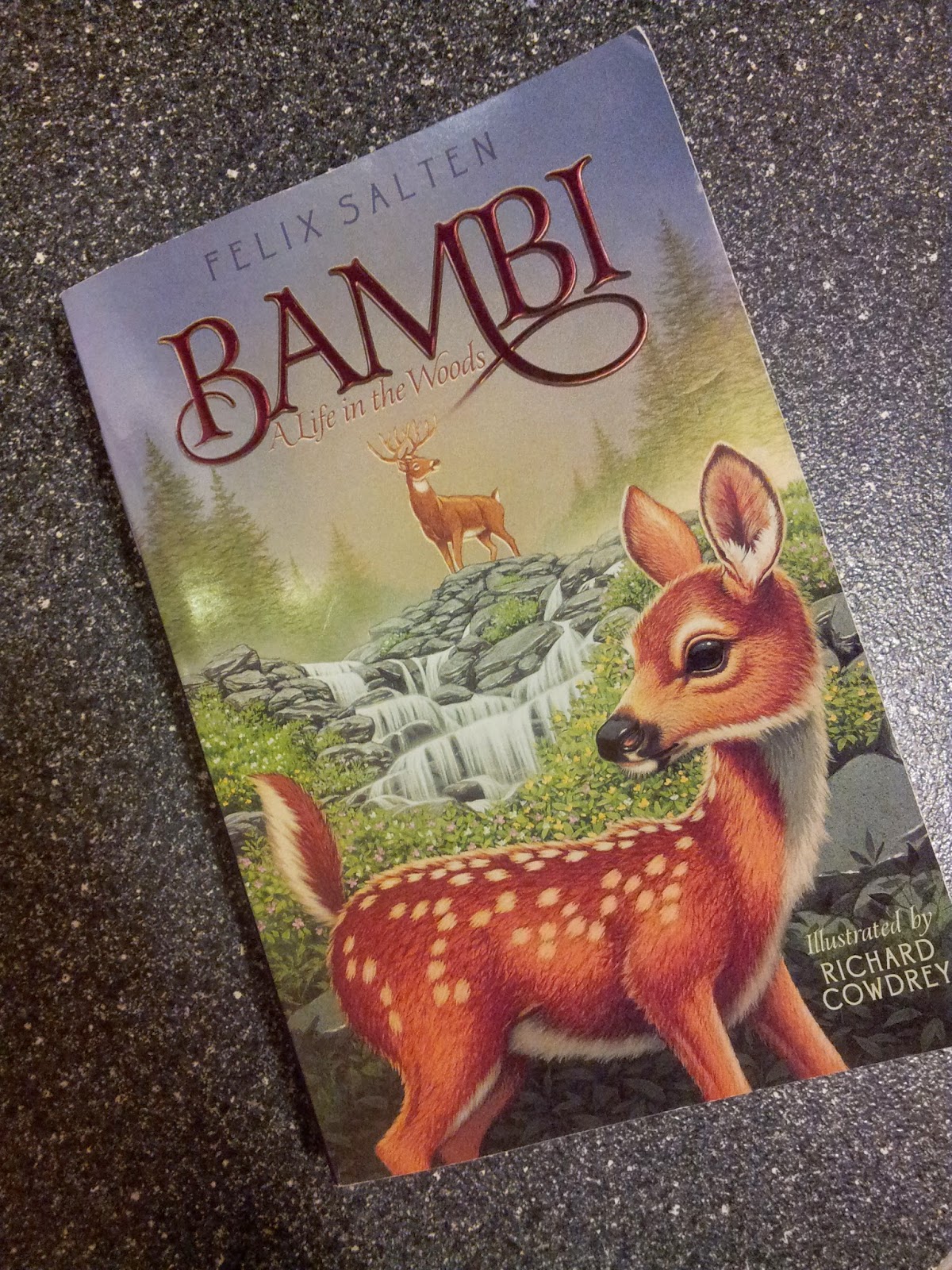

When Walt Disney released Bambi in 1942, it seemed to erase all

memory of its wonderful source-material, the novel Bambi, A Life in the Woods, written by Felix Salten (1869-1945) in 1923.

This is a great shame because in nearly every way imaginable, the novel is

infinitely superior to the admittedly classic film.

The

Disney film greatly softens the material, providing Bambi with amusing

sidekicks and expanding the action with comic set-pieces. Though there is an emotionally wrenching

scene where Bambi’s mother is shot by hunters, it is not overall a somber or

lachrymose film. Indeed, it is one of

the most limpid and lovely Disney films of the era.

This is

very different from Salten’s novel (originally translated into English by Whittaker Chambers). There, Bambi is born into a world of largely

absent fathers, continual threat from hunters, fierce competition for food and

resources, and the bitter reality of death.

The

lessons of Bambi are that life is often hard, and frequently entire populations

become the sport of the casually cruel and powerful. (As Salten himself would learn under the

Nazis.) Bambi particularly in his

romantic maturation, often behaves badly himself, as if Salten is saying that

we are born into a world where we are hardwired to be selfish and destructive.

While

reading classic children’s novels, it is easy to think of their adult

counterparts. (For example, Kenneth

Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows is

the Jane Austin novel of the

field). The prose of Bambi, with all its

simple, declarative force and echoes of an incantation, made me feel as if I

were reading an anthropomorphic book of the Old Testament.

It is

also a remarkable meditation on mortality and loss. While the film focuses on the death of

Bambi’s mother, the novel’s most eloquent rumination on death comes between two

leaves, anxiously discussing their upcoming fall. Here’s a brief excerpt:

“Can it be true,” said the first

leaf, “can it really be true, that others come to take our places when we’re

gone and after them still others, and more and more?”

“It is really true,” whispered the

second leaf. “We can’t’ even begin to imagine it, it’s beyond our powers.”

“It makes me very sad,” added the

first leaf.

They were silent a while. Then the first leaf said quietly to

herself. “Why must we fall?”

The second leaf asked, “What happens

to us when we have fallen?”

“We sink down…”

“What is under us?”

The first leaf answered, “I don’t

know, some say one thing, some another, but nobody knows.”

The second leaf asked, “Do we feel

anything, do we know anything about ourselves when we’re down there?”

The first leaf answered, “Who

knows? Not one of all those down there

has ever come back to tell us about it.”

Salten

was a very prolific author, publishing about one book a year on average. He is believed to be the anonymous author of

the erotic novel Josephine Mutzenbacher

(1906), which is about a Viennese prostitute.

Clearly a man of versatile literary achievements.

Like

many Jewish artists, he fell into Hitler’s crosshairs; Der Fuhrer banned

Salten’s books in 1936, and the author fled to Switzerland two years

later. He would die there.

Salter

sold the film rights to Bambi to director Sidney

Franklin for a mere $1,000; Franklin then sold the rights to Disney. As is often the case with Disney and

copyright, they would argue in the 1950s that the book was in the public domain

and attempt to retain greater profits.

(Disney evocation of copyright always struck your correspondent as

risible, considering they have made millions of dollars adapting public domain

fairy tales. Perhaps the scariest

sequence of any Disney film happens in business meetings away from the camera.)

Adults

who consider a “children’s novel” with trepidation should have no fear. No less than John Galsworthy wrote that: Bambi is a delicious book. Delicious not only for children but for those

who are no longer so fortunate. For

delicacy of perception and essential truth I hardly know any story of animals

that can stand beside this life study of a forest deer.

We

cannot argue.

Tomorrow -- the return of People’s

Symphony Concerts!

No comments:

Post a Comment